Dinner in the Diner During the Golden Age of Rail Travel

Omaha and Council Bluffs Branches

Two thousand and nineteen was the sesquicentennial anniversary of the driving of the golden spike for the transcontinental railway, with Omaha being the starting point for the Union Pacific Rail Road. It got me to thinking of dining by rail in the golden age of railroads in the United States during the 1930's, 40's and 50's. It is fascinating to follow the development of fine dining while traveling.

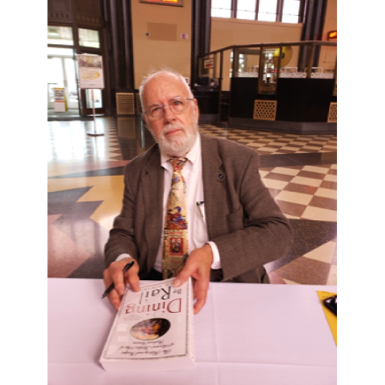

Author James D. Porterfield came to Omaha's Durham Museum, the old Union Pacific terminal, to discuss the topic. His book, Dining By Rail, details the history of rail car dining and has 330 recipes developed by the railroads as well.

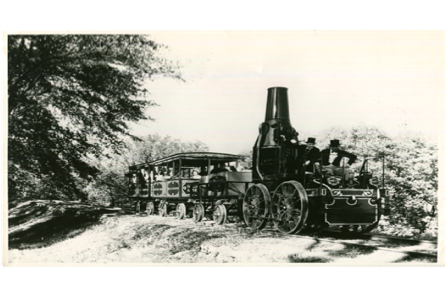

There was little thought given to dining well in the earliest days of rail travel. Patrons sat in open coaches, eating more soot and ash from the engine than anything else. Food was an afterthought. The trains themselves had to be constantly resupplied with wood and water. During these stops, passengers had about 20 minutes to gulp down whatever was available, and the food was unfailingly horrible. Bitter black coffee, stale bread nicknamed "sinkers," and dry, tough, salty ham may be a passenger's fate. In addition, with such a short time available, it was mob action getting to the food provider: a mad dash to buy something, choke it down, and get back on the train, saving the indigestion for later. Many passengers brought their own box lunch to avoid eating the wretched fare available at the rest stops. "News Butchers" were the next refinement. Boys would get on the train at one stop, sell their wares of apples, sweetmeats, candy, books and newspapers by going up and down the aisles, then get off at the next stop so they could work the train returning to their home station. News Butchers were universally condemned as being highly unsatisfactory.

There was little thought given to dining well in the earliest days of rail travel. Patrons sat in open coaches, eating more soot and ash from the engine than anything else. Food was an afterthought. The trains themselves had to be constantly resupplied with wood and water. During these stops, passengers had about 20 minutes to gulp down whatever was available, and the food was unfailingly horrible. Bitter black coffee, stale bread nicknamed "sinkers," and dry, tough, salty ham may be a passenger's fate. In addition, with such a short time available, it was mob action getting to the food provider: a mad dash to buy something, choke it down, and get back on the train, saving the indigestion for later. Many passengers brought their own box lunch to avoid eating the wretched fare available at the rest stops. "News Butchers" were the next refinement. Boys would get on the train at one stop, sell their wares of apples, sweetmeats, candy, books and newspapers by going up and down the aisles, then get off at the next stop so they could work the train returning to their home station. News Butchers were universally condemned as being highly unsatisfactory.

The railroads then tried station houses. These would be restaurants subcontracted to provide food at a railway terminal. One of the best was the chain of Fred Harvey Houses, staffed with the Harvey Girls, around 1870. Their territory covered the USA Southwest. Fred offered above average food that was fresh and homemade, for a reasonable price. The eggs, for example were never refrigerated. He recruited respectable women, the Harvey Girls, who were paid $17.50 a month, to provide the service. These women were unmarried, agreed to work for six months, and were given room and board with a 10:00 p.m. curfew overseen by a matron. Many Harvey Girls married their customers. The Harvey establishments were a symbol of efficiency. A brakeman would notify passengers two stops ahead that there would be Fred Harvey service: a dining room for six bits, or lunch counter and pay a la carte. He would determine the number who wanted to eat and telegraph that ahead one stop before the eating stop. Fred was perhaps the inventor of the fast food industry.

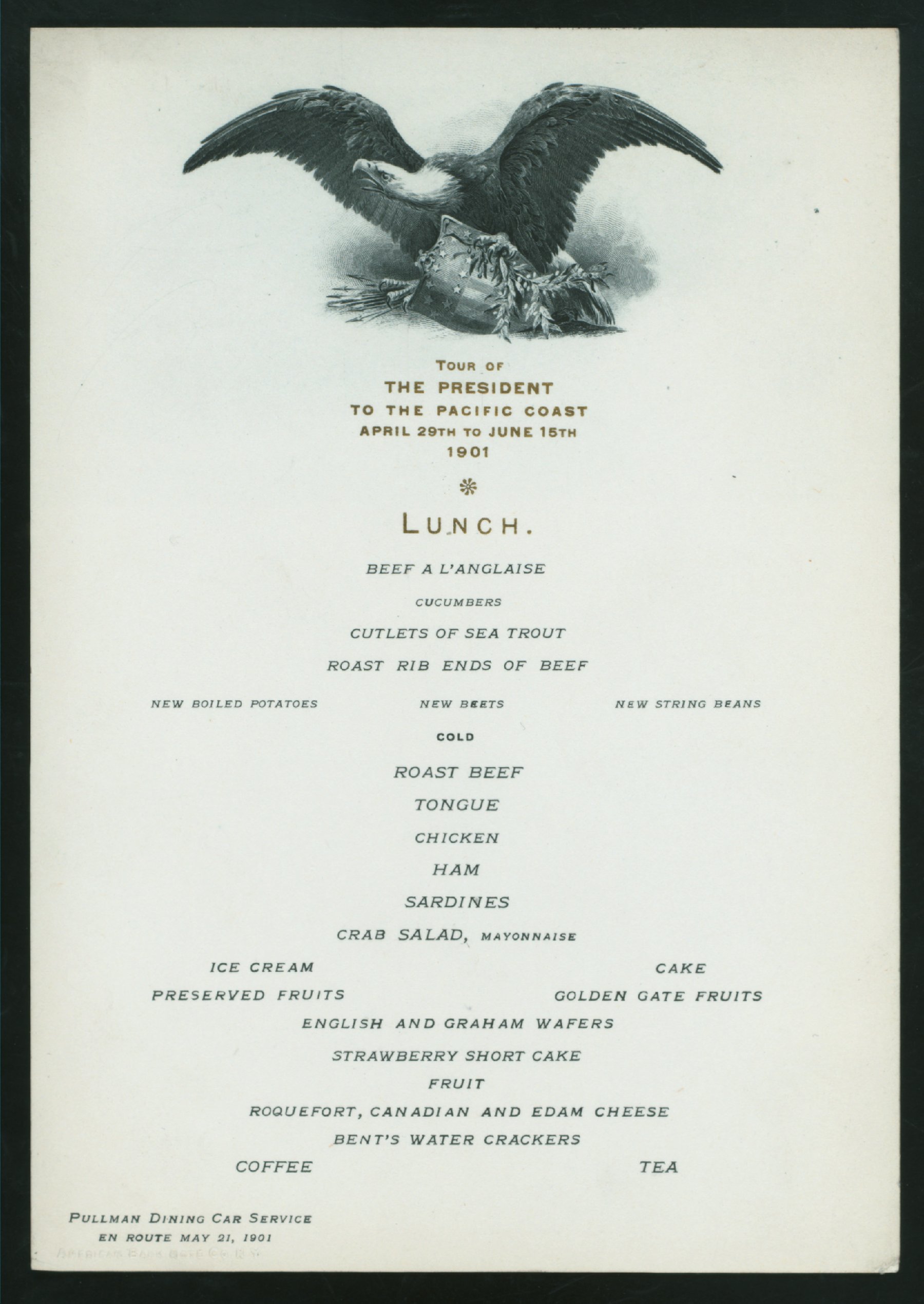

As good as the Harvey chain was, the passenger was still only given a limited amount of time to eat and re-board his or her train. The first written account of a meal served on a train was in 1842, when the President and Board of Directors for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad were served a cold meal. It was not until the Civil War that food was routinely served on hospital trains. These were just box cars fitted out for food preparation. They included a kitchen, cupboards,

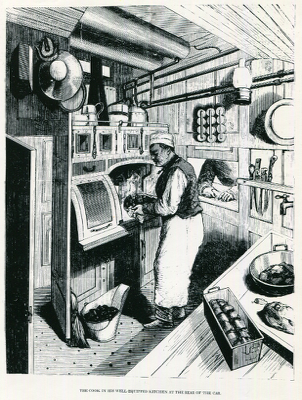

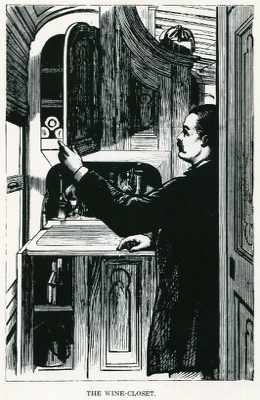

sink and storage compartments. In 1867, George Pullman, who had introduced the Pullman sleeping car two years before, came out with his 'hotel-car.' It was the first rail car designed specifically to prepare food. The hotel-car offered all the amenities of a hotel while on a protracted journey. They had a 3 foot by 6 foot kitchen, a wine closet, and a pantry operated by a crew of four or five. More beer and wine was stored under the floorboard. These cars cost $24,000.00, a fortune in those days, and carried 1,000 napkins, 150 table cloths, china, glassware, 133 food items, enough for up to a seven day trip. The conductor walked around taking orders from a large menu, and the meal was served on tables temporarily fastened to the wall. It was royal luxury to the passenger of that time. Service was provided by white clad, impeccably clean waiters. But there was still a problem. How do you get to the dining car? It was a dangerous endeavor as one had to jump over the gap between car ends while the train was moving and twisting. In 1887, George Pullman invented The Sessions Vestibule. An elastic diaphragm mounted on a steel frame and held firm by powerful springs allowed the passenger to easily and safely walk right over the gap.

Still, despite all the advancements in rail car dining, many lines resisted investing in dining cars. Although they were wildly popular, they were also tremendously expensive. Ultimately, it was good old fashioned competition that persuaded the railroads to get on board with dining cars. The Union Pacific broke an agreement with Burlington not to have dining cars with its 1889 announcement that it would, in fact, have dining cars. This was only 20 years after the driving of the golden spike. Competition for passengers was fierce, and first class passengers would invariably select a line with a dining car over one without. By 1929, lines were also adding air conditioning.

The dining car was a marvel of organization. From its humble beginnings of 60 feet long, modern cars turned into a length of 200 feet. Railroads developed their own logo marked china and extra heavy silver plated flatware. Re-equipping the cars was a never ending job, done with great skill. Only the highest quality of beef, veal, mutton, poultry, fish or pork was selected. Dairy and fruit items were of the best quality. They were always on the lookout for unusual items that a consumer could not get at home. For example, The Great Big Baked Potato was touted by the Northern Pacific. They discovered that large Yakima Valley potatoes were being fed to the pigs because, at 5 pounds, they were too large and were considered impossible to bake.

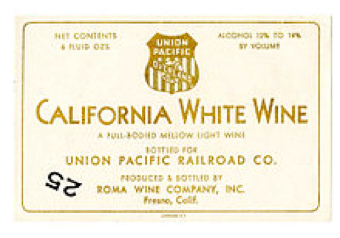

A two pound spud was deemed ideal, but larger than we typically get today. The secret to baking was to deeply pierce each end with an ice pick and add a pan of water in the oven to replace lost moisture. Other lines promoted their French toast, Dover Sole, Whitefish, Wenatchee apples, Lobster Newburg On Toasted Cornbread, steaks and the like. The Wenatachee Valley apple (Rome Beauty) was promoted by Great Northern for their large size and delicious taste, and special dishes were promoted using the apples on the train. Railroad lines would contract for food and beverage items. For example, the Union Pacific joined forces with the Roma Wine Company in the 1940's to private label white wine.

Amazing food came out of these small, cramped, very hot kitchens (up to 125°), where, on cross country Limited Trains, they would have to produce three meals a day. The chefs were very innovative. Bisquick was invented by chefs of the Southern Pacific and revolutionized American eating habits. An executive of General Mills was astounded how quickly he received an order of hot biscuits and asked the chef how it was done. The chef told him he blended flour, baking powder, salt and lard together, then put it in an ice chest for later use. Seeing the commercial, potential General Mills then turned it into a Betty Crocker product for sale to average consumers, and it didn't have to be refrigerated. The Pullman Loaf was sandwich bread baked in square, straight sided pans so that all sides were the same size. This enabled better stacking and storing of the loaf in a crowded kitchen than regular rounded top, beveled sided loaves. To keep bacon from curling up and breaking, it was first partially cooked in the oven to break the grain of the meat, then placed in the broiler to finish. Thus prepared, it laid flat on the plate without crumbling or curling. Menus were unusual, but not so far away from what patrons were used to lest they be afraid to order an item. One of the unusual recipes was Cantaloupe Pie on the Texas & Pacific Railway and can be found in Porterfield's book.

Other railroad innovations include the Presto Log. Developed by Weyerhaeuser for the railroads. the logs were made by combining sawdust and wax under pressure. They were originally used as backup supplies for heat in case a train got stuck in the mountains in winter. They were clean burning and provided good heat. Bottled water also was a railroad innovation. A T&P Chef was disciplined for not topping off his car's water tanks in some small Texas town where he was instructed to do so. He objected because the water always had a red tint to it. Another line, the B&O, owned the Deer Park spring and resort near present-day Oakland, Maryland, and served and used that spring's water in their dining car service.

Patrons loved the combination of luxury, top quality food while moving and viewing an ever changing panorama of scenery. Especially desirable were the domed SKY VIEW cars that featured a glass dome above the regular roof of the dining car. Impeccable service started with the commissary loading the train. Perishable foods were packed in watertight containers and packed in ice. One hour before departure, any meat grinding was done to guarantee freshness. The cleaning crew had already washed down the walls and floors, wiped the tables and vacuumed the carpets. As the dining car was taken to the train, the chefs began preparations: baking bread, roasting meats, prepping desserts and vegetables. Waiters would set the tables with linen, dishes, silverware and glasses, placing a silver vase of fresh flowers on each table. Uniforms were spotless.

Typical evening dining seating was offered at 5:00, 6:00 and 7:00. Meals might be announced by a waiter using chimes, passing out menus or posting a sign for each cabin. Water and coffee were offered to the diner upon arrival to the dining car, as well as menus, order forms and pencils. The waiter tore the top copy of the two part order form off and submitted the order to the kitchen. He then delivered bread, salads and the like. A steward prepared alcoholic mixed drinks or opened wine. Attentive service was provided throughout the meal: delivering the courses and clearing the table. At the end of the meal, the waiter discretely handled payment and customers moved on, perhaps to the lounge, or back to their waiting seat. Then the process was repeated for the different sittings. After the passengers were fed, the staff of porters, conductors, brakemen were served. Finally, the dining car crew got to eat. Restocking the train occurred during stops at different terminals. Dining cars did not typically accompany the train for its full destination. They would be dropped off on a side rail after the eating service was over and be taken back to its city of origin or its next drop off point.

Rail dining, however, was always a loss leader for the railroads. By 1937, the average meal on the Pennsylvania RR sold for $1.24, while its true cost to the RR was $1.61, creating a loss of $1 million. By 1949 the loss was $4 million, and by 1957 it rose to $29 million. The railroads considered low cost meals as an advertising expense. If they raised the price to break even, it would be higher than the finer restaurants and hotels and customers would balk. The Great Depression reduced ridership and passenger funds available for meals. World War II further curtailed dining by rail, and after the war, most rail travel was intercity, not cross country. In the 1950's, trains had to compete with buses, automobiles and air travel. By May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over America's passenger rail travel. Rail car dining ceased altogether in 1983, but has started up again in certain areas.

But the memories remain. What was it that made dining on a train such a memorable experience? It was a combination of the "miraculous quality to the service of a freshly prepared four-course meal from the confines of a dining-car kitchen" and the romance of travel. Mark Twain described this as "an exhilarating sense of emancipation from all sorts of cares and responsibilities." And that feeling was enhanced by being on a train, being served high quality, delicious food, as spectacular scenery passed by, viewed behind large windows. Literally, a movable feast.

Postscript: There are still a few working dining cars in existence today. The Napa Valley Wine Train provides wine and gourmet dining. The Texas State Railroad has a dining car. The San Diego Winery Train offers a fine dining with wine luncheon. There is also My Old Kentucky Dinner Train out of Bardstown, KY, which operates in Bourbon country. The Golden Dome from Denali to Anchorage still has a dining car, but east of the Mississipi, they are discontinuing the dining cars on overnight trips. Outside the USA, there are also some dining cars still providing service, such as the Orient Express.

Source: Dining By Rail by James D. Porterfield, Saint Martin's Griffin, New York 1993.