Agoston Haraszthy: American Entrepreneur & Founder of California's Oldest Premium Winery

By Tom Murnan

Council Bluffs & Omaha Branches

Agoston Haraszthy was a fascinating individual who contributed greatly to the development of wine in the United States. He was a restless, energetic optimist, a self promoter whose ambitious ideas and actions resulted in dizzying heights and abysmal failures in his life. Facts are intermingled with fiction as the Haraszthy legend was promoted by Agoston himself and his sons to enhance his persona. Faced with contradictory facts and stories, I decided to go to the definitive guide on Agoston's life: Strong Wine The Life And Legend of Agoston Haraszthy. Written by Brian McGinty, Agoston's great-great-grandson, who meticulously researched what many call the Father of California Viticulture. The book separates fact from legend as best it can, and explains the many twists and turns of this fascinating pioneer from Hungary who so influenced winemaking in California.

Although born to a noble Hungarian family of modest means, he did not hold the title of Count. People of his time gave him the honorary title of Colonel. Legend says he was a Royal Hungarian Body Guard. There is no evidence of that. He was not the private secretary to the Archduke Joseph. He was not a political refugee. These things all embellished a mystique that he loved to promote. His son said he brought Zinfandel to California. There is no written proof of this. But the man did found the first premium winery and built the first stone winery buildings in California, and brought European vitis vinifera grapes to the state. His life was one of stellar highs and deep lows.

Agoston was born on August 30, 1812 in Pest, Hungary to Károly (Charles in English) Haraszthy and Anna Mária Fischer. As was the custom of aristocratic families, the boy was named after the nearest saint's feast day in the Catholic Church, which was Saint Augustine of Hippo. So, the English translation of Agoston would be Augustine, but he never anglicized his name as his father later did. The Haraszthys were one of the oldest noble families in Hungary, but were not titled. They were not part of the great landowners of Hungary. He received a classical education and could speak about 5 languages. His father had a small estate in the southern part of Hungary in the plains area called the Bácska, the agricultural heartland of Hungary, which included vineyards, but the area was not known for making great wine. There is no record of exactly what grapes the Haraszthys raised, but the area had Olaszrizling (Italian Riesling) and Cirfandli, a red grape now thought to be Zinfandel, and the Kadarka. Although not a particularly good wine growing area, the Bácska was near the celebrated Tokaj-Hegyalja region where the world renowned Tokay wine was made. Besides making wine and growing grain, the estate raised silkworms.

Eleonora Haraszthy

In 1833, at the age of 20, Agoston married Eleonora Dedinszky of Polish descent. It was considered a desirable match. Their first child, Gaza, was born eleven months after the marriage on the family estate at Bács County. The couple went on to have a total of six children. The other children's names are: Attila, born 1835 in Bács; Arpad born 1840 at Futtak, Hungary; Ida, born in Illinois in 1834, Bela born 1846 in Wisconsin and Oteila, born 1848 in Wisconsin.

The aristocracy was absolutely tradition bound at that time, and rarely made changes in social or economic life. Most changes had to be approved by their overlords, the Hapsburgs, in Vienna. Young Agoston found this to be stifling. He had dreams of making a name for himself. After reading the writings of Count István Széchenyi, who wanted Hungarians to throw off the old feudal ways, reading about America in an 1834 book by Sándor B. Farkas entitled Travel in North America, and meeting an English naval captain and two Americans, Agoston convinced his cousin Károly Fischer to accompany him to America, leaving Eleonora behind with two children and pregnant with a third. He considered the United States as the land of opportunity.

Stopping first in London, he was amazed at the vitality and wealth of the English capitol. He kept a journal of his travels. The two landed in New York and made their way to Wisconsin at the end of April, 1840. The Wisconsin Territory was the frontier of the United States then, a land of opportunity. After traveling through the woods, waterways and prairies, they discovered a beautiful spot about 26 miles northwest of Madison, on a high hill overlooking the Sauk Prairie where the Wisconsin River flowed past. Struck by this gorgeous panorama of nature, he named it Szeptaj (Beautiful View). Paying $400.00 he purchased the best spot of land. He then found an investor, Robert Bryant, who had the capital to help him found a village which he named Haraszthy Town (now Sauk City), the first incorporated village in Wisconsin. With his financial partner, he begun an amazing number of businesses to attract settlers: a grist mill, a sawmill, a brickyard, a store, a ferry and a steamboat, and a hotel. He planted a vineyard for himself as well as grain. As a farmer he raised pigs, horses, cattle and sheep, selling the wool to others. All this took about two years.

Agoston returned to Hungary to bring his wife, children and parents to the new world. Partly to promote his new village in Wisconsin, Agoston wrote a 550 page book in Hungarian about his adventures entitled Utazás Éjszakamerikában (Travels in North America). This was not just a journal of his travels from New York to Wisconsin, but also included some imaginary characters and a fanciful account of Indian life on the Great Plains. He praised the American institutions and values. For example, one could travel freely through the different states, something you couldn't do in Europe. Plus there was liberty and democracy. It was only the second book ever written in Hungarian about the United States. He was probably hoping for Hungarian emigrants to come to Haraszthy Town. He left Hungary in 1842. Arriving in Haraszthy Town the family lived in a house that he had built.

Agoston threw himself energetically into promoting all his business ventures. He became a U.S. Citizen on July 18, 1843. He was a staunch Democrat. During this period his mother died, and his father, who began using the name Charles instead of Károly, at the age of 38, remarried an American woman, Emma Rendtorff. Charles was an educated man, could speak 12 languages and was a chemist. He served as a pharmacist for the pioneer community. The Wisconsin winters were not kind to his European grape vines. They could not withstand the cold Wisconsin winters. When gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in 1848, he left Wisconsin for California.

Although he was behind in his debt repayment and had some health issues, neither of these would account for the rather sudden decision to leave for California. It is speculated that perhaps the warmer and more suitable winemaking environment in California was found to be most attractive. He wanted to settle, not go for gold. He liquidated his holdings in Wisconsin and took a wagon train to California. Agoston had five big luggage wagons drawn by fifteen teams of oxen, and a horse drawn wagon that he drove. They went across Iowa down to Saint Joseph, Missouri and joined the Santa Fe Trail. They began the trek about April first, 1849. Officers were elected and Agoston was chosen captain. They crossed the Kansas and Arkansas rivers and on several occasions shot buffalo for food. Passing through the Oklahoma panhandle, they entered New Mexico, arriving near Santa Fe on July 17th. But there was still the relatively unknown Gila Trail that they needed to take to San Diego. This was the most difficult leg of their journey.

The Haraszthys landed in San Diego City in December, 1849, population about 600. California was still governed by the laws of Mexico. Agoston launched a number of business and agricultural projects, such as a stagecoach line, a livery service, fruit orchards and butcher shop. He planted a vineyard just outside San Diego, near the mission of San Luis Rey, with grape cuttings imported from Europe. On April 1, 1850, the first election under the American system in California took place and Agoston was elected Sheriff and city marshal of San Diego. His father Charles was elected Commissioner of City Lands. The vineyard did not do well, however, because the weather was too uniformly warm all year long.

In 1851 he was elected to the California State Assembly. Eleonora, however, decided she wanted to return to New York for the proper education of five of the youngest children. She settled in Plainsfield, New Jersey, 25 miles west of New York City. Agoston was not to see her and those children for five years. Agoston took Attila, now 16, with him up north. There he met the former General Mariano Vallejo who was in charge of the Mexican holding of California until the Bear Flag Revolt on June 14, 1846, where the General was captured and deposed.

In March of 1852 he sold all his holdings in San Diego and bought 50 acres of land near Mission Dolores, two miles south of San Francisco, naming it Las Flores. He again planted an orchard as well as vegetables, grain and grapes. The vineyard had cuttings from Europe, and perhaps some Zinfandel. Unfortunately, the weather was foggy and too cold to ripen grapes. He sold half of Las Flores to purchase new land. In 1853, he tried again in San Mateo County, at a place called Crystal Springs, planting the Mission grape and vitis vinifera grapes on 640 acres. Interestingly, Eleonora had met a fellow Hungarian in New Jersey, General Lázár Mészáros, who had a nursery with fruit trees as well as grape vines. He lived about two miles away from Eleonora. Arpad, who was living in New Jersey at the time, recalled years later that Mészáros had sent vines to Agoston, some probably coming from the William Prince nursery in Fushing, NY. The Prince catalogue had a listing called Black Zinfardel [sic] that came from the Bácska, making it likely that both Agoston and Mészáros would be interested in this grape variety. There was, however, no hard proof that Zinfancel was sent to California by General Mészáros.

In June of 1854, it was discovered that the land on which Agoston had founded Crystal Springs in fact belonged to a Domingo Feliz, so he was forced out of that property. He made claim to a new 640 acres. Besides, the area was not good for grapes. It was too windy, foggy and quite cold.

About this time Agoston decided to get into the gold refining business with some partners. He quickly learned about refining, especially since his father was skilled as a chemist. In 1854, with the Federal Government establishing a mint in San Francisco, he became the first U.S. assayer in California (through his political connections) and his father Chares became assistant assayer. In 1857 he was accused of embezzling $151,500. He had to resign his position at the mint and liquidate his properties to place funds in a trust during the investigation. It took until 1861 to finish the legal proceedings, but was ultimately exonerated.

Buena Vista Winery

In 1856, Representative Mariano Vallejo had invited Agoston to Sonoma to try his wines made from the Mission grape. Impressed, Agoston bought a small winery that in 1840 belonged to Mariano's brother, Salvadore, from the current owner, Julius Rose. The property had not been profitable, and Rose lost his mortgage to a W. R. McReady, who now owned the other half of the property. Early in 1857, Agoston paid Rose $11,500.00. Since land was cheap, he eventually expanded his holdings to about 5000 acres (most of it not planted to grapes), built an impressive villa, and named the property Buena Vista, the Spanish version of Szeptaj (Beautiful View). Today it is considered the first premium winery in California. It seemed to have everything he wanted: terroir, great sun exposure and perfect weather. Eleonora and the younger children returned to California in 1857 to join Agoston, Attila and Gaza in Sonoma. First, Agoston bored two tunnels, using Chinese labor, into the side of the foothill, and built a temporary wood press house. The first tunnel was completed in 1857 and was twenty feet wide, seven feet tall and one hundred feet long. The second tunnel was started in the autumn of 1858 and was twenty feet wide, ten feet high and one hundred feet long. These tunnels became aging chais, keeping the wine at a steady 55° to 60°F. Eventually, around 1862, two limestone buildings were built at their entrances. The buildings were made from the stone debris from the tunnel. These were the first hillside tunnels dug in Sonoma. He used Chinese labor partly to save money, but also because the Chinese were hard workers. A white worker would charge $30.00 a month for labor, while the Chinese worker cost $8.00 for the same work. He was criticized for this by the Shovelry wing of his own Democratic party, who had been fermenting racial tensions when Agoston was in the legislature in 1852.

Buena Vista Winery

The winery was the first gravity flow winery in California. He had the latest wine equipment and hired Charles Krug as winemaker. He also built a villa for himself on the property. Unlike his neighbors who planted on the valley floor, he planted his vines on the hillsides without irrigation. Hillsides provided protection from spring frosts which affected the valley bottom, they made it possible to vary the exposure to the sun as well as the wind, and hillsides were less apt to be composed of heavy clay soil. Besides, Sonoma received an annual rainfall amount of 25 inches, which was adequate for the vine. More watering would only dilute the intensity of the fruit. The European varieties of vines for Buena Vista came from his Crystal Springs property, including Zinfandel according to a recollection from Arpad years later. In February and March of 1857, Agoston planted 16,850 vines. His first vintage in 1857 yielded 5,000 gallons, with wine selling for $1.00 to $1.50 a gallon. He also made 120 gallons of brandy, and 60 gallons of tokay which he did not sell. In addition he had 65 tons of table grapes to sell. By 1858 he added 40,000 more vines, of these, 26,000 were European (known then as foreign) vines and 450,000 Mission vines. By January of 1859, he added another 100 acres under vine. To supplement income from wine, he also raised cattle on the higher lands, planted 350 acres to wheat and sold fruit from the orchards.

Harvest at Buena Vista Winery

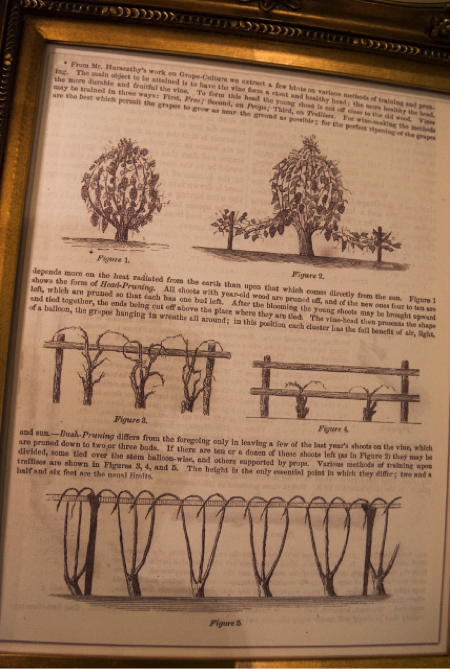

Agoston was constantly experimenting with viticultural practices, wine blends, and dry-farmed hillside plantings. He promoted using redwood for barrels, which was plentiful and cheap at the time. He founded the California Viticultural Society and in February 1858 wrote a 19 page monograph titled Report on Grapes and Wine in California. This became the definitive reference guide to growing grapes and making wine for many immigrants. He insisted on using vinifera grapes. The report conveyed his enthusiasm for grape growing and ended with an exhortation for the government to get involved with winemaking. His wines began winning awards. In 1860, Agoston entered the Sonoma County Fair where he won first prizes for the best white and the best brandy. At the 1860 State Fair, he entered 35 bottles from 1857, 1858 and 1859. He won six first place prizes and one second place for wine. Wines at that time were primarily the Mission grape, and foreign wines were blended in with the Mission grapes. Wine varietals were not written on bottle labels until the 20th century. If Zinfandel was used, it was not documented. Despite his successes, Agoston was still not satisfied with his wines. He felt that Sonoma had the potential to become California's greatest wine growing area.

One of his ideas of improvement was to establish a horticultural society with a garden to raise trees, plants and vines. The Sonoma and Napa Horticultural Society was incorporated by selling stock to investors. Land was purchased about a mile from the Sonoma town square and corn, peaches, walnuts and almonds were planted along with European vines. He offered to sell off portions of Buena Vista to small winemakers. For twelve acres, a fledgling winemaker could have a vineyard of 6,800 vines, with two acres left over for buildings and a garden, all for $2,140.00. Larger offerings were also available. Only three individuals purchased property in 1859, including his former neighbor at Crystal Springs, Charles Krug. But the number of horticulturists began to increase and by October 1860, there were 40 grape growers in Sonoma, including ex-Governor William Boggs, General Mariano Vallejo, and his two sons, Gaza and Attila Haraszthy. Not all had purchased land from Agoston. This added up to 1,161 acres owned by the horticulturists community. In the winter of 1860-1861, he created a test vineyard to see which foreign grapes would thrive on the hillsides and in the California weather. Besides all his other projects, Agoston formed another company, the Sonoma Tule Land Company, investing money to drain the marshland in San Pablo Bay and remove the dense reeds, called tules, and convert the land into farming land. He also helped establish a steamship line to travel between San Francisco and Sonoma.

As a member of the California State Agricultural Society, he had been working on a resolution for the legislature to urge the state to send a commissioner to Europe to collect and purchase grape stock to bring to California. That commissioner was to write a report of his observations and have the state pay the cost associated with purchasing and shipping the vines back to California. The legislature accepted the Society's proposal, with a few changes, and the Governor signed the measure. In 1861, Agoston was appointed by Governor John G. Downey to a three man commission to explore the best way to promote the grape vine in California, provided that the office holders did not ask or receive any pay. Agoston interpreted this as he could ask for his expenses to be reimbursed, but would not receive a salary. He wanted to expand the diversity of wine grapes grown, find the best varieties of rootstock and encourage winemakers to experiment.

Agoston, Eleonora and Ida arrived in Paris in July of 1861 where he joined up with Arpad. His son had been studying at Madison de Venoge in Champagne. The Haraszthys then went to Dijon and visited a garden with 600 varieties of vines. They went to Gevrey and Chambertin, Beaune, the Close de Vougeot and other areas in the Côte d'Or, taking detailed notes. He then went to Germany to explore Riesling vines. Then it was on to the Rhône, Piedmont and the town of Asti, where he tried both the still and sparkling wine. The sparkling wine made him ill. The consul general of Holland happened to be on the train with him and told him that Asti was known for this. It was poorly fermented and the peasants put honey in the wine to make it sweet. Riding the train after drinking sparkling Asti caused stomach discomfort. Bordeaux was next, where he toured the House of Alfred de Luze. There they sampled the excellent wine at de Luze and the surrounding area. They stopped at Château Margaux where he noted the close vine spacing of only three feet apart. But he also noticed a number of withered vines. Perhaps this was the start of phylloxera which had begun already. The Haraszthys left Bordeaux for Madrid, taking a horse drawn diligence, designed for 20 people, through the mountains. From Madrid they traveled south to Málaga where they made a sweet wine from dried raisins. Returning to Paris in October 1861, Agoston alone traveled back to California. Eleonora and Ida remained in Paris for awhile, and Arpad resumed his studies in Champagne.

Agoston's vines did not return to San Francisco until January 23, 1862. All arrived in good condition, transported by Wells Fargo. He had purchased 100,000 cuttings and 350 grape varieties. A catalogue assigning a number and listing the grape varieties is filled with names unfamiliar to the modern reader. For example, vine number 265, a Malvoisé d' Aragon from France, is unknown today. More familiar grape varieties were Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Riesling, Chardonnay (not identified as such but probably in with the Champagne grapes), Carignane, Grignolino, Gewürtztraminer, Merlot, Mataro, Muscat de Frontignan, Pedro Ximenes, Sémillion, Sauvignon Blanc and others. Many of these varieties are staples of a modern vineyard today. The name Zinfandel was not among those listed varieties, but could have been hiding, listed under a local name, like number 418 Red Szilvânyi.

Agoston had borne all the expense himself, including travel, cuttings and shipping, amounting to $8,457 just for vines and $1,549 for shipping. A motion to reimburse Agoston was presented to the legislature where it died in committee. The original commission specifically stated that the commissioner would not be paid. When a vote was taken, the mining counties outnumbered the agricultural counties, and their vote followed the original provision that no reimbursement would be made. This was a huge financial blow. He had to take out three large five year mortgages. Nonetheless, the 1862 importation of vines was a significant event in the history of California wines. Agoston initiative promoted the fact that winemaking was an economically important industry and only vitis vinifera should be used in California. His dream of a European-like state sponsored botanical garden where vines could be made freely available had been rebuffed.

Left to his own devices, Agoston began selling cuttings to the general public himself, building up stock on the more popular grapevines. In April, 1862, Agoston was elected as the president of the California State Agriculture Society. At the State Fair, he gave a speech describing the progress made in agriculture. He also supported the use of Chinese immigrants, who had done so much work in his vineyard. Some politicians were trying to ban them from entry into the state. Also in 1862, Agoston had written a book for Harper & Brothers in New York called Grape Culture, Wines and Wine-Making, With Notes upon Agriculture and Horticulture. The 400 page book contained notes he had taken on his trip to Europe, and comparisons of European and Californian vineyard practices. In the autumn of 1862, Eleonora returned to Sonoma with Arpad. Ida stayed behind in Paris. He had completed his studies in Épernay and was eager to make still wine as well as champagne at Buena Vista. He took a still white from the 1861 vintage and started the process of making it a sparkling wine. Gaza, the oldest son was serving in the Union Army back east, fighting in the Civil War.

Arpad Haraszthy

Meanwhile, Agoston began a third tunnel, wider and longer than the first two. A 54 foot by 64 foot stone gravity flow press house was made from the limestone removed from the tunnel. Large redwood beams supported the second story. A steam powered crusher could handle 50,000 pounds of grapes a day. All of Agoston's sons except Gaza were employed by Buena Vista. About this time, Attila and Arpad began making frequent visits to General Mariano Vallejo's house at Lachryma Montis to visit his daughters Natalia and Jovita. Also in 1862, the steamship company Agoston was a partial investor and guarantor to began running regular routes from San Francisco to Sonoma and back. Christened the Princess, it could make a one way trip in three hours.

Agoston wanted to keep improving Buena Vista but was unable to continue sinking capital into the company by himself. He had $93,000 in three outstanding mortgages at the time. In 1863 he converted Buena Vista to an agricultural corporation with stockholders, with 6000 shares at $100.00 a share. It was renamed the Buena Vista Viticultural Society (BVVS). This was a risky venture. He would now be under the scrutiny of other stockholders who could question his actions. Agoston owned 43%. The money was used to make improvements: a 50 horse stable, a small railroad to run grapes up the side of the hill to the second story of the press house, pipes, pumps and machinery for a distillery, pumps, and a champagne house. Agoston was the superintendant in charge of every day operations. Arpad was hired as the champagne maker. Attila also worked at BVVS.

On June 1, 1863, two of Agoston's sons married two of General Vallejo's daughters. Sonoma's two most prominent families would be united, twice. Attila married Natalia, and Arpad married Jovita on the same day in a dual ceremony. Father Peter Deyaert, the padre on horseback, united the couples at Lachryma Montis, and a reception was given there as well. Attila and Natalia moved to Attila's vine covered property near Buena Vista, and Jovita and Arpad lived in a small house built by Arpad in a ravine, also near Buena Vista.

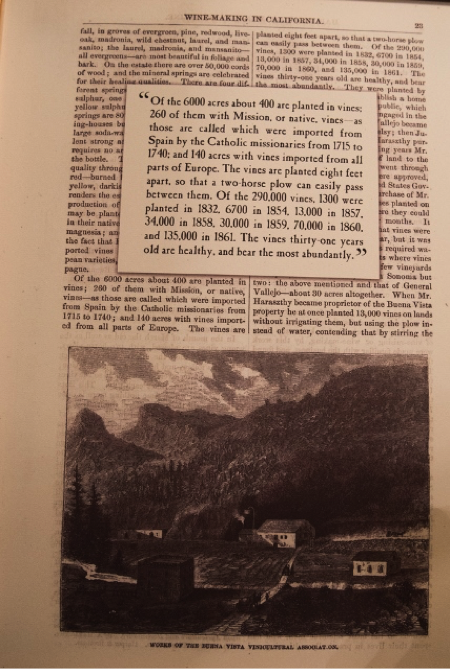

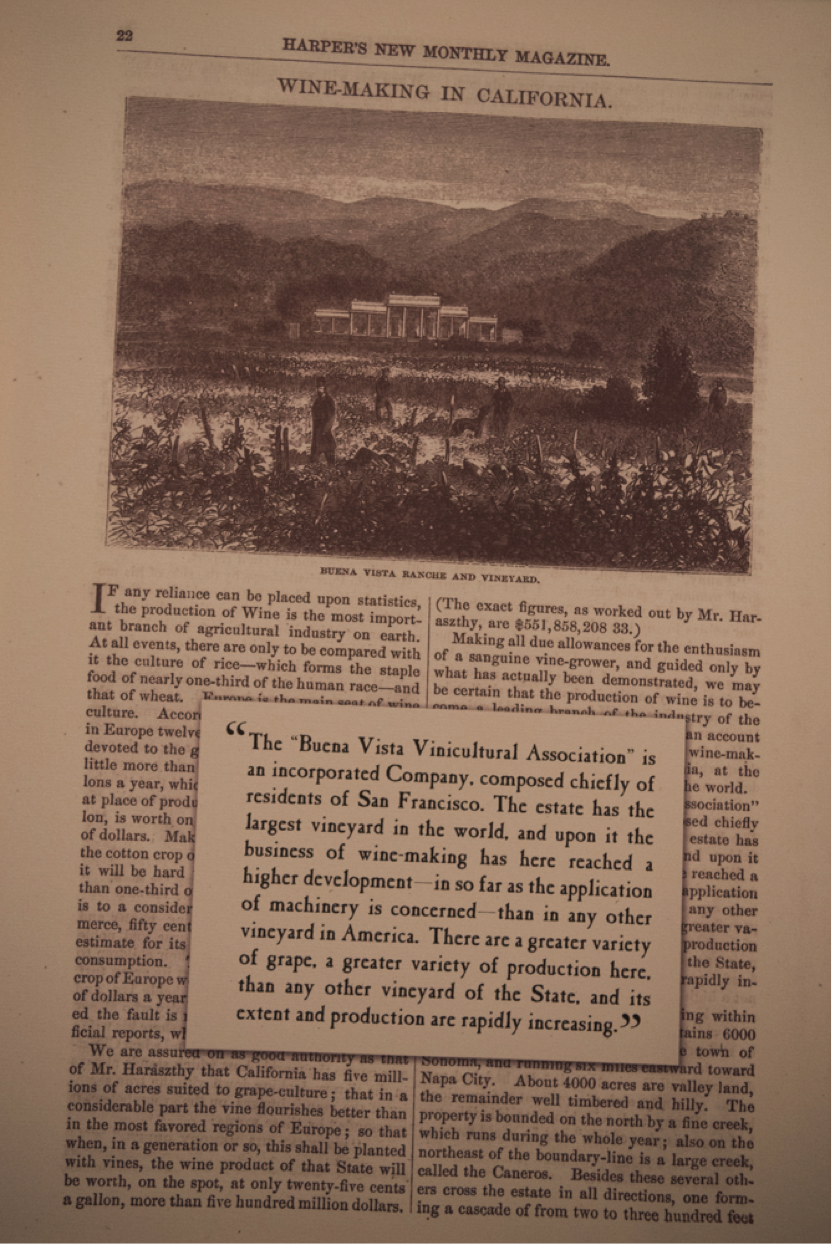

In 1864, Agoston traveled to New York to meet some of the investors in BVVS. He addressed the American Institute's Farmers Club and spoke about the wine industry in California. There he brought with him an article, which was later printed in the San Francisco Mercantile Gazette, which spoke of wine production in 1856. He received another large loan from railroad tycoon Cornelius Garrison for $40,000.00. Ever the promoter of California viticulture, the Atlantic Monthly out of Boston published an article named California as a Vineland and an article in Harper's Monthly entitled Wine Making in California. This article, replete with wood cut illustrations, can be found at Buena Vista today. When he returned to California, he was informed that Gaza's regiment had been captured in Mississippi by Confederate troops on April 25, 1864. He was imprisoned in Tyler, Texas.

|

|

1864 Harper's Monthly article on the Buena Vista

Viticultural Society Wine Making in California

By 1865, the Buena Vista Viticultural Society had 645 acres under vine. But trouble was brewing. A series of financial reversals had accumulated. Arpad's first champagne vintage did not sparkle and the board fired him. Embarrassed, Agoston reimbursed the BVVS $6,000.00, a costly mistake. In 1864 a drought lowered production. The Federal tax on brandy went up and the price of wine went down. Cost from improvements were expensive. Agoston, who had studied vine spacing during his trip to Europe, undertook to change the traditional spacing at BVVS where vines were spaced apart eight foot on center. The garden at Dijon, however, had done studies and determined that the optimal spacing was one foot apart. Agoston decided that at BVVS, optimal spacing should be four feet apart. He decided to achieve this by a method know as layering. This involves digging a hole and bending a vine cane into the hole and covering it back up, exposing two buds to the air. Eventually, in about three years, the cane will grow its own roots while it still got nutrients from the parent. At that point, the link could be severed and the vine could sustain itself. You may wonder why Agoston didn't just plant a cutting in the existing vineyard. Just putting a cutting in a mature vineyard has a high failure rate, but the layered method has a greater survival rate. Repeat the process annually, and in about seven years the entire acre could have the new, tighter spacing. In the winter of 1864-1865, Chinese laborers layered 260,000 vines. So instead of the usual California method of 680 vines per acre, you would end up with 2,722 vines. His neighbors thought he was crazy, but he defended his position in a February 1866 essay of California Rural Home Journal.

Harper's Monthly entitled Wine Making in California with

Agoston's former white villa in the background.

Planting closer together would avoid the problem of grapes of low sugar, poor color and less flavor. It would also help poor farmers who had little monetary resources get the most out of their acre of land. These assertions caused a lot of controversy among Californian winemakers. He also was narrowing down which European varietals would work best in California. Unfortunately, there was no mention of when Zinfandel was first crushed at Buena Vista. By 1866, Zinfandel was beginning to be recognized as a superior grape variety for California. In the winter of 1865-1866, Agoston did not spend much time with every day duties at BVVS. He returned east to Washington to successfully lobby Congress to lower the tax on brandy and wine.

Ida Haraszthy Hancock

In February of 1866, Agoston's daughter Ida married a wealthy older man named Major Henry Hancock in the large house at Buena Vista. They moved to the Los Angeles area where he had property where oil was oozing out of the ground. This he profitably sold as pitch for roofing. 1866 also marked the return of Gaza from his Confederate prison. He achieved the rank of Major, and was mustered out of the service in May, 1866. By this time, Attila had quit working for BVVS, and Arpad had been fired. Bela was an accomplished winemaker in his own right as well. The brothers made a new company called Haraszthy Brothers which supplied grapes to a company called I. Landsberger & Company of San Francisco, where Arpad also worked making champagne. Agoston was spending less and less time at BVVS, no doubt distancing himself from the enterprise, aware of his growing debt and significant problems at the vineyard. BVVS had never made a profit, and there were questions about the vineyard management there, especially because of the practice of layering which many critics felt was foolish. BVVS had 5,000 acres of land, but most of it was not under vine. One bit of good news was that BVVS had finally produced a first class champagne, but this had taken three years to achieve.

Buena Vista Viticultural Society in 1865

But most devastatingly, phylloxera began to noticeably infect the vineyards of Sonoma in 1866. As early as 1860, Agoston had noticed the occasional vine had wilted, and that the roots looked diseased. It took a long time, however, to identify just what the cause was because the louse would move on when the vine died and there was no evidence left to see. During all this time, Agoston took out loan after loan, using the only security he had, his BVVS stock. Finally, he simply had no more stock, so he filed bankruptcy in 1867. He stayed in the area until February, 1868. On January 5, 1869 his petition for bankruptcy was fully discharged. At the age of 54, had little to show for all his work in California.

BVVS hired a new superintendant, an Emil Dresel who had a nearby vineyard. Dresel was convinced that the cause of the vineyard wilting was due to Agoston's layering. He thought the crowded conditions led to weakening of the vines, and so began pulling out all the layered vines. But since Dresel had no real understanding of why the vines were dying, this did not solve the problem of dying vines.

Ever the entrepreneur and opportunist, Agoston's next venture involved leaving the United States for Nicaragua. This time his plan was to raise sugar cane and distill rum to sell in the USA and make enormous profits. In February 1868, Agoston and Gaza took a ship to Nicaragua to examine the country. The country was a tropical paradise, full of orange, papaya, mango and cashew trees, as well as coffee and cocoa plantations. Obtaining new capital, and getting exclusive rights from the Nicaraguan government to distill brandy and rum for 20 years, Agoston began building facilities. He asked Eleonora, who was still in Sonoma with her children, to join him in the hot, humid, dangerous jungle environment. Two months after she arrived, she died of yellow fever, contracted by a mosquito bite, on July 15, 1868. Agoston had to return to California to settle Eleonora's estate. He signed papers on January 6, 1869. His 79 year old father Charles wanted to return with him, but he was not in the best health, having contracted dropsy. Afraid that Charles would fret himself to death if he didn't come, he was allowed to accompany Agoston to Nicaragua. But the hot, humid climate aggravated his dropsy. Charles decided to return to California but died on ship and was buried at sea on July 22, 1869 before arriving back in California.

Agoston was planning to build a sawmill on the banks of a river, but when he got to the site, he wanted to move the mill to the other bank. He needed to talk to the foreman, but the foreman was not around at the time. He took off his oilcloth coat and another coat and laid it down on the ground with his watch, presumably to take a nap while waiting. But he never returned home. When his family came to find him, the coats were on the ground and his mule was tied up with his pistols still in the saddle, but there was no Agoston. Looking up they saw a tree that spanned the river with a newly broken branch. Since an alligator had dragged a cow into the stream a few days before, it was speculated that the limb broke as he was trying to cross. He probably fell into the river and was most likely eaten by an alligator. No clothing or any remains were ever found. He was just 57 years old.

This painting hanging at the Buena Vista Winery was taken from an 1861 photo of

Agoston Haraszthy before he left for Europe in search of European grapevines.

BVVS continued to struggle. Good wines were made in the 1870's under the names of El Dorado Claret, Sparkling Sonoma, Buena Vista Golden Hock and Pearl of California, but the effects of phylloxera increased, not only at Buena Vista but at all California vineyards. It wasn't until 1873 that a man named Oliver Craig looked at the withered roots of one of his sick vines with a microscope and saw the tiny insects. Encumbered by mortgages, BVVS sold its vineyards and buildings in 1878 to Robert and Kate Johnson for $46,502.00 in gold. The Johnsons were not interested in wine and built a four story mansion on the property. The old wine cellars were used as carriage houses. The 1906 earthquake cracked the walls of Agoston's stone buildings and collapsed the tunnels. Later, Agoston's white villa and the Johnson's grand house both were burnt to the ground. By 1920, the State of California took possession of the property for unpaid taxes. In 1943, Frank H Bartholomew, vice president of United Press, bought the core of the old estate at auction, unaware of its provenance. Informed of its history, Bartholomew set out to again make wine, using the famed André Tchelistcheff as wine consultant. Bartholomew sold Buena Vista to a Los Angeles company, but kept the surrounding land. When Robert died, his wife Antonia built a replica of Agoston's villa and in 1980 founded the Frank H. Bartholomew Foundation on a 500 acre park that once had been Agoston's vineyard. After the Bartholomews, Buena Vista had a series of owners until it was purchased in 2011 by the Boisset Family Estates, whose roots are in Burgundy, France. The original buildings have been faithfully restored, and the wines are top rate.

Assessment of Agoston Haraszthy is difficult because one has to separate fact from the fiction of the Haraszthy legend. Besides his many self-promotions, there is still the question of whether he did, in fact, bring Zinfandel to California. In the 1970's, wines historians have arisen who dispute that Agoston was the Father of California Viticulture. They say he was not the first who brought vitis vinifera to California, and certainly was not the first to bring Zinfandel to the state. If you remove all the hype, a number of facts remain. Agoston was a force of nature, a vital energetic man who did a tremendous amount to promote wine in California. Besides his many writings, he brought numerous quality European vinifera grapes to the state, whether or not he was the first to do so. He promoted and modernized the industry while at the same time promoted his own self. As to the second question of whether he introduced Zinfandel, there is no hard proof in the form of written documentation to establish that he was the first to bring Zinfandel to California, but it is still possible because of the many local names (Cirfandli) Zinfandel had, and the multitude of cuttings Agoston brought back from Europe in 1862. It has always been hard to separate fact from fiction with Agoston Haraszthy, but he believed whole heartedly in the California wine industry and tirelessly promoted it.

Sources: Strong Wine The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy by Brian McGinty Stanford University Press 1998; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agoston_Haraszthy; https://www.buenavistawinery.com/about-us/the-entire-story; http://www.inn-california.com/articles/biographic/haraszthybio.html

Bronze Plaque of Agoston Haraszthy at Buena Vista Winery

-

Articles

- Cuisine of the Sun: Cuban Cuisine and Restaurants in Greater Miami

- The “American Riviera” Santa Barbara – splash, scenery and splendid sipping!

- The beginning of a love affair to remember – Thomas Jefferson ❤ Wine

- John Locke: politician, philosopher... oenophile?!

- The splendid wines of Virginia

- Ten tips for dining out: Refining our favorite pastime

- Lady Swaythling and The IW&FS

- The 1870 cellar of Charles Dickens

- A delicious history - Gelato past to present

- The splendid wines of Portugal

- One Oenophile’s Opinion . . . On Cellar Temperature

- Tasting the grape styles of California

- Building a wine cellar – don’t be afraid!

- Vancouver Dreaming

- Is it coffee–or is it Puerto Rican coffee?!

- Matching Wine with Food

- Malbec, the Summer grilling wine

- Champagne on the Rocks?

- Sauvignon Blanc - Better than Chardonnay in wine-food pairings?

- The Origins Of Our Great Society

- An Evening with Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson - A Summary

- Auguste Escoffier: Founder of Modern Cuisine

- Island Traditionalists and a Mainland Maverick Wines of Dalmatia

- Eastern Europe Wines & Dining

- Wines of Croatia Part II

- Agoston Haraszthy: American Entrepreneur & Founder of California's Oldest Premium Winery

- Rare Discovery of 18th & 19th Century Madeiras at Liberty Hall

- Left Over Wine?

- Dinner in the Diner During the Golden Age of Rail Travel

- Missing The Boat