Auguste Escoffier: Founder of Modern Cuisine

by Tom Murnan (Council Bluffs & Omaha Branches)

I was dimly aware of the name Auguste Escoffier just a few months ago, but if I had been asked to give any kind of summary of his life or importance, I would have been unable to do so, other to say he was an pioneer in French cuisine. I suspect that most members of the IWFS are in the same situation. Serendipity can be a wonderful thing, and it was quite by chance that I stumbled onto an entertaining, and at the same time, educational presentation of Escoffier at Omaha's Institute for the Culinary Arts which presented a brunch and one-man play on his life. It's hard to know where you are going if you don't know where you've been, and the whole time I was watching the play I was thinking that I must bring this wonderful presentation to my fellow IWFS members.

After a series of articles promoting the history of Escoffier in our Bluffs Gazette, the Council Bluffs Branch engaged local Omaha Actor Marty Skomal to bring Escoffier to life. Our event featured a dinner with all Escoffier recipes paired with all French wines. The one man play is delightful, fitting right into the second part of our IWFS name: FOOD, and its mission to educate its members about the world of food and wine.

Marty Skomal as Escoffier with member Tom Murnan

Marty Skomal as Escoffier with member Tom Murnan

discussing hotel magnate César Ritz

This man was a giant in the culinary world at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Escoffier met with, and impressed, the important people on the world stage at that time: King Edward VII, Kaiser Wilhelm II, actress Lily Langtry, hotelier César Ritz, and opera superstars Nellie Melba and the divine Sarah Bernhardt. When Ritz ran the London Carlton, and Escoffier ran its dining room, together they changed English society's dining habits. It became more important to be seen dining at the Carlton than to stay and eat at home. From the play we learned about his relationship with these luminaries, the challenges of his day, and his culinary accomplishments. The character of Escoffier came alive and spoke directly to you as if you were having a tête à tête in his home in Monte Carlo.

Marty Skomal (Escoffier) is a graduate of the conservatory of theatre arts at Webster University. A native Omahan, he has been an arts administrator with the Nebraska Arts Council for 25 years, as director of programs for the last ten. Previously he was director of theatre at the Jewish Community Center, production manager at Chanticleer Theatre, and has worked with many local and regional theatres including the Nebraska Theatre Caravan. As a director, Marty has directed for the play lab of the Great Plains Theatre Conference at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha. He has performed Escoffier in Omaha previously at Le Voltaire Restaurant, for the Institute for the Culinary Arts at Metropolitan Community College, and in Lincoln for the Angels Theatre Company. Marty wishes to thank Barbee Davis, who directed and wrote a large portion of the production, for her unwavering support in bringing Escoffier from conception to reality.

Marty is willing to travel, so if your branch would like to do something unique, fun and educational, contact Marty at mjsomaha@yahoo.com regarding his play Escoffier: Master of the Kitchen.

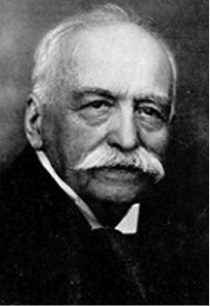

Actor Marty Skomal portrays Auguste Escoffier

Actor Marty Skomal portrays Auguste Escoffier

The following are the series of articles on the French culinary powerhouse, Auguste Escoffier that appeared in the International Wine & Food Society Council Bluffs Branch, Bluffs Gazettes from January 2014 to April 2014. They focus in greater detail on the life, times and importance of this great French chef.

I have noticed that in the International Wine & Food Society, at least in the United States, that we tend to emphasize more the Wine part of the name and place less emphasis on the Food. The two are inextricably intertwined, however, because without food to enhance the wine, and vice versa, the pleasurable experience of dining is diminished. I hope to help right the ship a bit with a series of articles on one of the towering figures of French cuisine. He never worked on an aristocratic estate but instead displayed his culinary skills in restaurants and the grand Hotels of the era. He is best known for promoting French cuisine during the Belle Époque in the 1890's.

I have noticed that in the International Wine & Food Society, at least in the United States, that we tend to emphasize more the Wine part of the name and place less emphasis on the Food. The two are inextricably intertwined, however, because without food to enhance the wine, and vice versa, the pleasurable experience of dining is diminished. I hope to help right the ship a bit with a series of articles on one of the towering figures of French cuisine. He never worked on an aristocratic estate but instead displayed his culinary skills in restaurants and the grand Hotels of the era. He is best known for promoting French cuisine during the Belle Époque in the 1890's.

Georges Auguste Escoffier was born October 28th, 1846 in humble circumstances in the French village of Villaneuve-Loubet, not far from Niece. He began his culinary career at the age of 13 in his uncle's restaurant. In those days, working in a kitchen was a hot thankless job. At the time, the culinary profession was not held in high regard. Kitchens were unclean, disorganized, and a safety hazard This was true of private aristocratic estate kitchens, as well as inns, taverns, and the newly developed place to eat, a restaurant. Young Auguste, as he preferred to be called, was not coddled but was given rigorous and disciplined training in his apprenticeship.

In 1865, he moved to Paris and began working for another restaurant, Le Petit Moulin Rouge. When the Franco Prussian War broke out in 1870, he became an army chef. Auguste noticed how the military was organized in a hierarchical system and thought he could apply this kind of structure to the kitchen to gain more efficiency, reduce duplication of effort, and identify specific staff functions. He organized what today is called the Brigade System with its clear chain of command. More on the Brigade system in the next Gazette. This streamlined division of labor proved to be very effective.

Auguste applied the Brigade system to the hotel kitchens he worked for. Moving to England in 1890, working with César Ritz, he transformed the Savoy Hotel in London, then the Paris Ritz (1898) and then the London Carlton Hotel in 1899. He invented new dishes for celebrity patrons who stayed at these hotels. The organized kitchen was essential to luxury liners such as the Titanic, and his menus inspired the last menu in the first class dining room when the Titanic sank in 1912. He met Kaiser Wilhelm II on board the SS Imperator who told him, "I am the Emperor of Germany, but you are the Emperor of Chefs."

Besides organizing the kitchen, Escoffier simplified the elaborate recipes and procedures of his predecessor, Antonin Carême (1784-1833). Carême was a pioneer in French Grande Cuisine. He worked closely with aristocrats like Talleyrand, the future King George IV and Tsar Alexander I, and wrote several cookbooks. He is known for large, intricate and decorative centerpieces and elaborate and involved recipes. Escoffier simplified Carême's classifications. For example, he distilled Carême's detailed classifications of sauce down to Five Mother Sauces. He believed that the grandeur of French cuisine came from the sauces.

Escoffier wrote eight landmark books, including his most famous, Le Guide Culinaire which is still used today and has over 5000 recipes. The Guide has been translated into English: The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery. Recipes stress using the freshest ingredients, local ingredients that are in season, and simplified preparation that allowed for flexibility that carries over to our time.

So, why are we concerned with a man whose heyday was over a hundred years ago? Because so much of what he did still remains with us. He abolished the system where all food came out at the same time and replaced it with its delivery in courses. He developed canning of tomatoes, vegetables and other methods of food preservation. He invented the bouillon cube. Kitchens became organized, cleaner, more hygienic and safer. He elevated cooking to an art and a profession that workers could be proud of. He was aware of social concerns in the kitchen. He created a kind of social security for his kitchen staff and was concerned about their welfare. He created recipes, such as Peach Melba, that are famous even in our time. He championed fresh, wholesome ingredients from farm to table. His cookbooks are still a foundation of French Haut Cuisine. He fed the poor because he did not believe in leftovers, preferring instead to start each day anew in the kitchen, and so donated what remained from the previous day to the hungry.

In his day, there was a lot of drinking alcohol and smoking in the kitchen. He banned smoking and drinking and even asked a French doctor to develop a healthy barley drink to relieve the unbearable heat of the kitchen. The toque or hat and neckerchief were introduced to prevent drops of sweat falling into the food. Most importantly, Escoffier brought a sense of calm and order to the kitchen. "Above all, keep it simple" is one Escoffier's famous maxims. His first concern was the pleasure and comfort of the customer.

Escoffier retired in 1920 and moved back to the Mediterranean area of France. He was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor. In retirement he continued to write, his last book, Ma Cuisine, dealt with cuisine bourgeoisie. He died at Monte Carlo, Monaco, on February 12, 1935, the pre-eminent chef of France.

Sources: On Cooking A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals 4th Edition by Sarah R Labensky and Alan M Hause; Wikipedia; History of Auguste Escoffier - YouTube http://www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DA6T7d2yB-2I; Escoffier: Britain's First Master Chef by Hannah Briggs http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/0/20123168

ESCOFFIER INTRODUCES THE BRIGADE SYSTEM TO THE KITCHEN

Continuing our miniseries on the important French Chef, Auguste Escoffier, we move to a significant improvement that he introduced that revolutionized how kitchens were organized.

When the Franco Prussian War broke out in 1870, Escoffier became an army chef. While in the service, Auguste noticed how the military was organized in a hierarchical system. He thought he could apply this kind of structure to the kitchen to gain more efficiency, reduce duplication of effort, and identify specific staff functions. He organized what today is called the Brigade System with its clear chain of command. This streamlined and reduced duplication of effort in hotel kitchens. There were two main divisions in a restaurant: The Kitchen Brigade and the Front of the House, or Dining Room Brigade. Each station has clear cut responsibilities. Today, with modern equipment, or a smaller establishment, the number of positions can be reduced. Maintaining a well-organized kitchen was key for Escoffier who could be managing up to 60 or 80 members of staff at any one time. The aim was to cut down on waiting times and to ensure that food was served efficiently at exactly the right temperature. Most importantly, Escoffier brought a sense of calm and order to the kitchen. The Brigade system is only for large kitchen staffs, but even smaller professional kitchens will adopt some portion of Escoffier's organization and division of labor even today.

The Kitchen Brigade

At the top was the Chef de Cuisine (executive chef), responsible for all kitchen operations and all those under him. He developed the menus, the theme of the restaurant and set the tempo and tone. Beneath him was the Sous-Chef, or second in command. He was directly responsible for scheduling the staff, placement and changing staff at the different stations, and sometimes relaying orders from the waiter to the kitchen. Next came the Chefs de Partie or station chefs (Commis). In the old system, duplication would occur at this point because each station made what they needed. You could have more than one station making the same sauce, for example. Now roles were clearly defined at each station.

The Saucier (sauté and sauce station chef) held one of the most important and exacting stations, demanding experience and expertise in making sauces and sautéing most dishes. The Rôtisseur (roast station chef) were responsible for roasting and jus. The Poissonier (fish station chef) was responsible for fish and shellfish. The Potager was responsible for stocks and soups. The Pâtissier (pastry chef) was responsible for all baked items, such as bouchées and puff pastry, and supervised the Boulanger (bread baker) who made rolls and breads. There was a Entremetier (hot vegetable chef), a Garde-Manger (pantry chef) responsible for cold food preparations, salads and cold appetizers, and a Chef Tournant, or relief chef. Under these chefs, responsible for a certain station, were the demi-chefs (assistants) and the Commis (apprentice), in English known as cooks.

The Dining Room Brigade

The front of the restaurant also had its hierarchy of authority. Even today, students at culinary institutes study both the front and the back of the house.

The Maître d'Hôtel, or Maître D, is in charge of the dining room and is responsible for operations in the front of the house. He or she trains and manages the service and wait staff, works with the Chef de Cuisine to develop menus, is responsible for the wine list, and seating of patrons.

The Sommelier or Wine Steward's duties include all aspects of the wine service: selecting and purchasing wines, printing a wine list, assisting guests in selecting the best wines based on customer preference, price and affinity for the food selected, and the proper opening and serving of the wine. Wines may need to be decanted at tableside. Some restaurants have a Beverage Manager

The Chef de Salle, or Head Waiter, is in charge of the service and waiters for the entire dining room.

The Chef d'Étage or Captain deals with the guests once they are seated. He or she explains the menu, answers questions and takes the order. Should there be tableside food preparation, the Captain does it.

The Chef de Rang or Front Waiter sets the table for each course, ensured that the food is properly delivered, and that the guests' needs are promptly and courteously met.

The Demi-chef de rang or Commis de Rang (Busboy) fills water glasses, clears plates between courses, fills bread baskets and assists the front waiter or Captain as required.

Sources: On Cooking A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals 4th Edition by Sarah R Labensky and Alan M Hause; The Professional Chef 9th edition The Culinary Institute of America; Escoffier: Britain's First Master Chef by Hannah Briggs http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/0/20123168

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE FRENCH RESTAURANT: 18TH TO MID 20TH CENTURIES

Most people today have no clue as to how food in the past was prepared and served for the traveler, or just hungry diners with money, home or away from home. The professional trained chef is relatively recent in the historical scheme of things. The development of the restaurant as we know it only occurred at the end of the 18th century in France. Instead of one menu for everyone, this new innovation called a restaurant produced numerous dishes for different diners at different times of the day.

In much of Europe, and France in particular, food preparation outside aristocratic households was done by various guilds, who had a monopoly on certain kinds of preparations. One preparation was a "restorative," highly flavored and rich soups or stews. In fact, the word restaurant comes from the French word restaurer, meaning to restore. Their original purpose was to restore strength and vigor. So during the reign of King Henri IV (1553-1610) there were guilds for rôtisseurs who cooked main cuts of meat, vinaigriers, who made sauces, pâtissiers, who cooked pies and poultry, tamisiers who baked bread, and the like. Taverns and inns typically served food prepared by these guilds. Food was not the main focus of these establishments: drinking and a place to sleep was. Food was an afterthought, and there was a very limited selection. Food was prepared at the guild and brought in. Diners would share a common table and eat family style.

The first restaurant opened in Paris in 1765 when a tavern keeper, Monsieur Boulanger, hung a sign advertising his restorative: sheep feet in white sauce. After winning a lawsuit brought by a guild who thought they had the monopoly on soup and stew preparation, the restaurant went on to prosper. Boulanger's innovation was to focus on food, offer a selection of prepared food instead of just a preselected, limited menu, and the food was prepared on site as you waited. Since it was a restorative, it had a kind of medical application. As time progressed, this medical aspect was dropped in favor of a diverse selection of ordinary food.

During the French Revolution (1789-1799) the guilds were abolished, as well as the aristocracy. Their private chefs and kitchens were scattered, but some of the well trained, sophisticated chefs started restaurants.

The Grande Taverne de Londres opened in Paris in 1782 by Antoine Beauvilliers, the former steward to King Louis XVIII (1814 to 1824). His innovation was to offer food service during fixed hours as well as a printed menu. A wait staff was impeccably trained and patrons sat at small tables instead of a communal table.

|

|

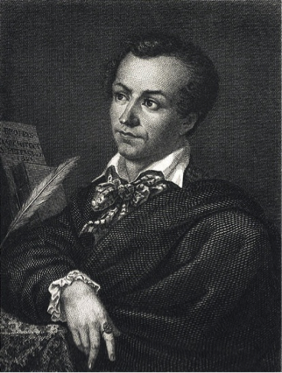

| Antonin Carême | Carême's elaborate presentations |

By the middle of the 19th century, several large, grand restaurants in Paris were serving elaborate meals which recalled the days of grande cuisine of the aristocrats. Antonin Carême perfected this trend of dozens of courses, elaborately prepared and painstakingly garnished and sauced. Cuisine had become an art form. There were not, however, just restaurants serving grande cuisine. Some restaurants combined grande cuisine with cuisine bourgeoisie to create a simpler menu.

César Ritz

César Ritz

In the late 19th century, hotels offered the finest restaurants. César Ritz opened restaurants, first in London at the Savoy, and later the Paris Ritz and London Carlton. He allied with August Escoffier to make the hotel restaurant a destination, the showpiece of his hotels. Escoffier refined and simplified Carême's cuisine, and organized the kitchen and wait staffs in a hierarchical system, with division of labor to make food preparation more efficient.. The first American internationally known chef, Charles Ranhofer (1836-1899) opened Delmonico's restaurant in New York City. Restaurants were now shaped into the form we are familiar with today.

English Women not allowed to dine in public circa 1890

In England, Cesar Ritz and Auguste Escoffier were brought over to the Savoy Hotel in London by owner Richard D'Oyly Carte, the impressario of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. Ritz wanted to make the Savoy's restaurant a magnet for London society, not just the luxurious appointments of the hotel. When they arrived, women seldom dined out. Highborn women would instead dine at their estates. Even for the men, dining out was mostly done at one's club, not a restaurant. Ritz worked to change that. He knew that men and women dressed up and dined out frequently in Paris, Vienna or the Côte d'Azure, for example, but once one crossed the English channel, a different set of social mores ruled. Women did not dine out in public, nor was it proper to dine out on Sundays. Ritz started a campaign for dining in the evening after an evening of the theatre. He enlisted the help of Lillie Langtry, (former mistress of the future Edward VII and stage superstar) who helped to get the liquor licensing regulations changed so liquor could be served until 12:30 in the morning. Gradually, it became more chic for men and women to be seen at the Savoy Restaurant than in their own homes. But Escoffier's stoves were a key attraction in making the hotel restaurant a fashionable place to go. Sunday night dinners after the theatre, with society dressed to the nines, became the event of the week. At the Savoy Restaurant they mingled with actors and actresses (Sarah Bernhardt), opera divas (Nellie Melba), composers (Sir Arthur Sullivan) and other artists. So, Auguste Escoffier, one of the greatest French chefs in history, had a hand in getting women out of their homes and into public restaurants in England.

Sources: On Cooking A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals 4th Edition by Sarah R Labensky and Alan M Hause; Wikipedia.

http://www.famoushotels.org/article/1157 ; Wikipedia ; http://www.anothermag.com/current/view/88/At_the_Savoy_in_Mayfair

ESCOFFIER: THE FIVE MOTHER SAUCES

Our series on the influence Auguste Escoffier had on modern cooking continues with his classification of the five mother sauces. Sauces are the glory of French cuisine, and his predecessor, Antonin Carême had previously set forth four grandes sauces as the basis of French cooking: béchamel, espagnole, velouté, and allemande. Escoffier modernized this list with his five mother sauces by dropping allemande sauce, which is a variant of velouté, and adding hollandaise and tomato sauce.

Let's start by defining just exactly what a sauce is. A sauce is a thickened liquid used to flavor and enhance other foods. A good sauce adds flavor, moisture, richness and visual appeal. A sauce should compliment food. It should never disguise it A sauce can be hot or cold, sweet or savory, smooth or chunky. A mother sauce is the base or starting point for making other secondary sauces. Three of the mother sauces use roux, or flour and butter, as a thickening agent. A roux is equal parts clarified butter and flour, sautéed for various lengths of time. The longer you sauté it, the more brown it becomes. For a white sauce, you would sauté the roux for only a short time, for example, enough to take away the floury taste. Each sauce has a different flavored liquid as its base. Here are Escoffier's five mother sauces.

1. Béchamel Sauce is probably the simplest of the mother sauces because it doesn't require making stock. If you have milk, flour and butter, you can make a very basic béchamel.

Béchamel is made by thickening hot milk with a simple white roux. Clarified butteris the preferred fat to be used. Clarified butter is heated butter where the milk solids and water are poured off, resulting in a translucent golden butter fat.

The sauce is then flavored with onion, cloves and nutmeg and salt, then simmered until it is creamy and velvety smooth. Daughter sauces (secondary sauces) made from Béchamel sauce includes Mornay Sauce (cheese added), Crème Sauce (cream instead of milk) and Nantua Sauce (shrimp butter instead of plain clarified).

2. Velouté Sauce is another fairly simple sauce whose liquid can vary from chicken stock to veal or fish stock. Again, the liquid is thicken with a roux. Daughter or small sauces include Normandy Sauce (fish stock, chopped mushrooms thickened with egg yolk and cream) for seafood dishes, Mushroom Sauce, or Suprême Sauce (chicken Velouté Sauce with cream).

3. Espagnole Sauce, also known as Brown Sauce, is a more complex sauce. It starts with meat stock which was prepared with beef bones that were browned in the oven. This roasting adds a deep brown color and more flavor than if you just put the bones in water to make a stock. Espagnole also uses a roux, cooked until the flour is dark brown, but it then adds tomato purée and a mirepoix. A mirepoix is a mixture of finely chopped onion, celery and carrots. Roasting this vegetable mixture first adds even more flavor. Since Espagnole sauce simmers for a long time, the vegetables have time to release their flavors. Secondary sauces made from this mother sauce include Marchand de Vin Sauce (red wine sauce), Madeira or Port Sauces, Bercy Sauce (white wine and shallots) Mushroom Sauce, and Demi-Glace. Demi-Glace, the crown glory of French cuisine, is a reduction of half brown stock reduced by 50%, and half Espagnole sauce and is the basis of many meat sauces.

4. Hollandaise Sauce does not use a roux as its thickening agent. It is an emulsified sauce where the liquid is hot clarified butter and the thickening agent is egg yolks. An emulsion is a mixture of two liquids that would ordinarily not mix together, like oil and vinegar. In the case of Hollandaise, it is the lecithin in the egg yolks that acts as the emulsifier. Lecithin, a fatty substance soluble in both fat and water, will readily combine with both the egg yolk and the butter, essentially holding the two liquids together. Daughter sauces include Mousseline Sauce (whipped cream), Dijon Sauce (mustard), Béarnaise Sauce (tarragon leaves, shallots and tarragon vinegar), and Choron Sauce (tomato paste added to Béarnaise), and Mayonnaise.

5. Classic Tomato Sauce is the fifth mother sauce. This sauce resembles the traditional tomato sauce that we might use on pasta and pizza, but it's got much more flavor and requires a few more steps to make.

First the chef renders salt pork and then sauté aromatic vegetables. Then tomatoes are added along with stock and a ham bone, and simmered in the oven for a couple of hours. Cooking the sauce in the oven helps heat it evenly and without scorching.

Traditionally, the tomato sauce was thickened with roux, and some chefs still prepare it this way. But in reality, the tomatoes themselves are enough to thicken the sauce. Here are a few small sauces made from the classic tomato sauce: Spanish Sauce (sautéed green onions, green peppers, garlic and mushrooms), Creole Sauce (same as before but cayenne pepper and no mushrooms), and Provençale Sauce (sautéed onions, garlic, capers, olives and Herbes de Provence).

These five mother sauces, then, give birth to hundreds of other sauces. With the addition of different meats, vegetables, herbs and spices, these small or daughter sauces can enhance an infinite variety of food.

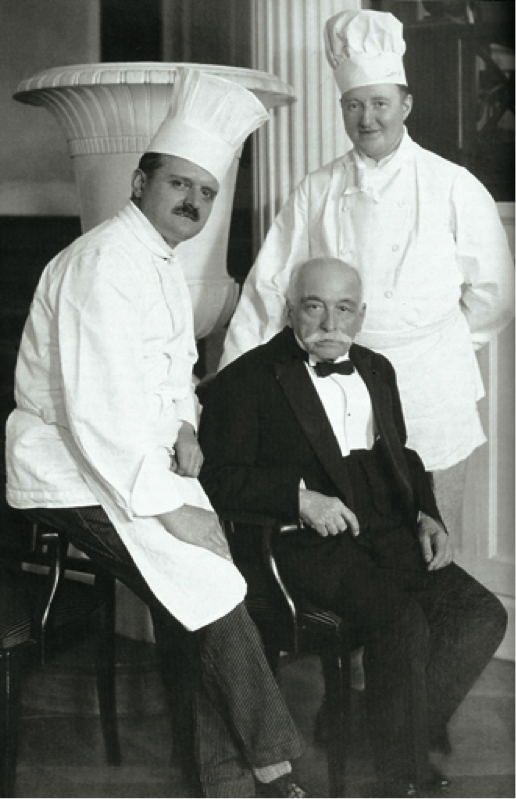

Auguste Escoffier (in black) with two of his chefs.

Auguste Escoffier (in black) with two of his chefs.

WHAT'S IN A NAME? ESCOFFIER'S ARTISTIC NAMES FOR FOOD

"That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet"

Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet

In my impecunious salad days, I was backpacking through Europe, staying at Youth Hostels and pensiones, having the time of my life. On this occasion, I was at a bargain restaurant in Brittany examining the menu. One item intrigued me: "Pommes Anglaise." Hmmm, I thought to myself, English Potatoes. The price was right (cheap), so I decided to take the leap to this obviously wonderful culinary experience. After all, it was French. When the plate was brought to table, I discovered that what I ordered was stinking lousy boiled potatoes! Was this potato sobriquet a scathing Gallic indictment of English cooking? Boiled potatoes indeed. A child of six could do it. This taught me to be a little more discriminating when examining floridly written menu items with exotic French names.

Having just completed our Escoffier event, it would be hard not to notice that most courses had a fanciful name. We learned in our one man play how Escoffier named two different items for the opera singer Nellie Melba: Melba Toast and Peach Melba. I thought I would run through the menu for the benefit of those who were not there, as well as to remind those that were, to learn more about how these foods got their names.

Cuisses de Nymphs à l'Aurore is perhaps Escoffier's most mysterious dish name. Nowhere does the name give a clue to what is in the dish. This subterfuge was purposely done. Thighs of the Nymphs of Dawn was euphemistically named to trick 600 guests at a soirée held in 1908 at the London Savoy for the Prince of Wales (the future King George V) into eating a food that was not popular with the English. The French, however, had been eating frog legs since prehistoric times. In fact, in the Tenth Century, French monks got frog legs classified as a fish to get around Lenten prohibitions on meat, and this classification has stuck in the culinary world to the present time. In some accounts, it is said that the prince was partial to frog legs, so he was in on the hoax. In other accounts he did not know of the deception and was not partial to frog legs either. The dish was served in a buffet with the above name so as not to disturb the delicate sensibilities of the diners, but really, Escoffier was miffed that the English would not eat a favorite French national dish. The dish was a sensation, and so Cuisses became a great hit that London social season. Imagine that. Setting your prejudices aside, through sleight of hand or just an iron will, could result in a wonderfully tasty dish.

Cuisses de Nymphs à l'Aurore is perhaps Escoffier's most mysterious dish name. Nowhere does the name give a clue to what is in the dish. This subterfuge was purposely done. Thighs of the Nymphs of Dawn was euphemistically named to trick 600 guests at a soirée held in 1908 at the London Savoy for the Prince of Wales (the future King George V) into eating a food that was not popular with the English. The French, however, had been eating frog legs since prehistoric times. In fact, in the Tenth Century, French monks got frog legs classified as a fish to get around Lenten prohibitions on meat, and this classification has stuck in the culinary world to the present time. In some accounts, it is said that the prince was partial to frog legs, so he was in on the hoax. In other accounts he did not know of the deception and was not partial to frog legs either. The dish was served in a buffet with the above name so as not to disturb the delicate sensibilities of the diners, but really, Escoffier was miffed that the English would not eat a favorite French national dish. The dish was a sensation, and so Cuisses became a great hit that London social season. Imagine that. Setting your prejudices aside, through sleight of hand or just an iron will, could result in a wonderfully tasty dish.

Melba Toast. If I told you that toast had been named after Helen Porter Mitchell, you would not recognize the significance. But if I told you that same toast was named after opera singer Dame Nellie Melba, you might remember that. Escoffier came up with this innovation in toast after the singer became ill in 1897 and wanted something light and simple to eat. César Ritz supposedly gave the toast its name after a conversation with Escoffier. It is simplicity itself. Lightly toast slices of bread, remove from heat source, trim off crust and split the bread in half, then toast the untoasted sides again. Melba toast is used even today in dieting, and for hors d'oeuvres as a base for spreadable toppings.

Melba Toast. If I told you that toast had been named after Helen Porter Mitchell, you would not recognize the significance. But if I told you that same toast was named after opera singer Dame Nellie Melba, you might remember that. Escoffier came up with this innovation in toast after the singer became ill in 1897 and wanted something light and simple to eat. César Ritz supposedly gave the toast its name after a conversation with Escoffier. It is simplicity itself. Lightly toast slices of bread, remove from heat source, trim off crust and split the bread in half, then toast the untoasted sides again. Melba toast is used even today in dieting, and for hors d'oeuvres as a base for spreadable toppings.

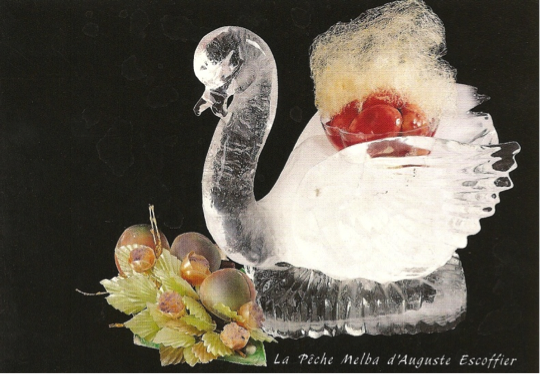

Peach Melba was created for the opera star when she was staying at the London Savoy Hotel, where Escoffier ran the restaurant. She was starring in Richard Wagner's Lohengrin. She gave Escoffier tickets to the opera, which featured a boat in the shape of a swan, and the next night he created a dessert for her. Peaches served over vanilla ice cream and topped with spun sugar were placed in a silver bowl and inserted into a ice sculpture formed in the shape of a swan. He called it Peach with a Swan. A few years later he refined the dish by removing the ice sculpture, and adding pureed raspberry as a topping. He then called it Peach Melba. There were many variations on this famous dessert, to which Escoffier commented in Memories of My Life “Pêche Melba is a simple dish made up of tender and very ripe peaches, vanilla ice cream, and a purée of sugared raspberry. Any variation on this recipe ruins the delicate balance of its taste.”

Tournedos Rossini. There is adispute as to which chef invented this dish: Marie-Antonin Carême or Auguste Escoffier. In Escoffier's cooking bible, Le Guide Culinaire, numerous recipes are named after Gioachino Rossini, enough to create a whole menu.

But my guess is that it was actually Carême who invented it, since Carême and Rossini were great friends. According to legend, the dish was named at the Café Anglais in Paris. Rossini insisted on overseeing the preparation of this dish near his table. The chef finally became fed up with his constant interference, whereupon the Maestro told him "So, turn your back." There are other versions on how the dish received its name, so we may never know for sure. But it is true that the combination pan fried tenderloin, served over a crouton topped with fresh foie gras, and garnished with demi-glace or Madeira sauce and topped with truffles is a classic gastronomic opus worthy of the maestro.

But my guess is that it was actually Carême who invented it, since Carême and Rossini were great friends. According to legend, the dish was named at the Café Anglais in Paris. Rossini insisted on overseeing the preparation of this dish near his table. The chef finally became fed up with his constant interference, whereupon the Maestro told him "So, turn your back." There are other versions on how the dish received its name, so we may never know for sure. But it is true that the combination pan fried tenderloin, served over a crouton topped with fresh foie gras, and garnished with demi-glace or Madeira sauce and topped with truffles is a classic gastronomic opus worthy of the maestro.

Bombe Nero was named after the Roman Emperor Nero, who began his reign in 54 A.D. after his uncle Emperor Claudius died. Legend has it that Nero fiddled as Rome burned during the Great Fire of 64 A.D. This was impossible since the fiddle would not be invented for another 1500 years, but Suetonius, in his The Lives of Twelve Caesars, mentions that Nero played the lyre. Despite being out of town during the fire, many of his enemies suggested that he set the fire to make room for an imperial palace.

Bombe Nero was named after the Roman Emperor Nero, who began his reign in 54 A.D. after his uncle Emperor Claudius died. Legend has it that Nero fiddled as Rome burned during the Great Fire of 64 A.D. This was impossible since the fiddle would not be invented for another 1500 years, but Suetonius, in his The Lives of Twelve Caesars, mentions that Nero played the lyre. Despite being out of town during the fire, many of his enemies suggested that he set the fire to make room for an imperial palace.

A bombe is a French frozen dessert made in a spherical mold. Layers of ice cream or sherbet would be spread on the mold and successively frozen before another layer was added. Finally, the mold was closed and frozen as a whole. In Escoffier's Bombe Nero a mold of vanilla ice cream, caramel and chocolate truffles was opened on to a punch biscuit. Meringue was piped over the ice cream and placed briefly in an oven to lightly brown the meringue. Once removed from the oven, flaming rum was ignited and the dessert was served immediately. It is the flaming rum that reminds us of Emperor Nero and his fiddling about while Rome burned.

So, the question remains: What's in a name? Apparently, a lot. An elegant name enhances a menu card. It can be used to disarm your prejudices and get someone to try something if only their narrow-mindedness would get out of the way (think of your kids...they won't eat pheasant but will eat "chicken"), and you can use a famous celebrity to entice someone to be adventurous. The next time you think that oysters are not indigenous to the Rocky Mountains, beware, be aware, and think what's in a name!

Sources: Wikipedia; http://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/opera-escoffier-and-peaches-the-story-behind-the-peach-melba/ ;

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/aug/07/frogs-legs-france-asia

(André L Simon, 1877-1970, The Concise Encyclopedia to Gastronomy, 1952)

WHAT'S IN A NAME PART 2: ESCOFFIER'S ARTISTIC NAMES FOR FOOD

In August 2014, the Omaha Branch put on their own event featuring the one man play: Escoffier Master of the Kitchen, A Play About the Most Influential Chef of all Time. With over ten thousand recipes in his repertoire, the menu designer has many choices to choose from. Here are some more stories behind the names Escoffier used for his recipes.

Velouté Agnès Sorel

R-rated mushroom soup! Although only the most dedicated American amateur history buff would recognize the name of Agnès Sorel, the French know her as the mistress to King Charles VII, who reigned from 1422 to 1461. It was a tumultuous time to be king of France, and Charles, beginning with the help of St.  Joan of Arc, eventually succeeded in ridding France of the English. He also received help from his wife, Marie d'Anjou, and her mother Queen Yolande of Aragon. Enter Agnès Sorel, who was his wife's lady in waiting and only 22 years old to his 40. She became the love of his life. She was exceptionally bright, politically astute, and incredibly beautiful. She was also said to have the most shapely and beautiful breasts in Europe. She was fond of wearing décolletage and gauzy dresses that showed off her considerable assets. One of the stricter moralist courtiers complained upon first meeting her that he could see her nipples! Pretty risqué for that era. When she became Charles' mistress, she had to give up being the mistress to two other courtiers (but she kept a third, the Royal Chamberlain and fellow advisor to the king, Pierre de Breze).

Joan of Arc, eventually succeeded in ridding France of the English. He also received help from his wife, Marie d'Anjou, and her mother Queen Yolande of Aragon. Enter Agnès Sorel, who was his wife's lady in waiting and only 22 years old to his 40. She became the love of his life. She was exceptionally bright, politically astute, and incredibly beautiful. She was also said to have the most shapely and beautiful breasts in Europe. She was fond of wearing décolletage and gauzy dresses that showed off her considerable assets. One of the stricter moralist courtiers complained upon first meeting her that he could see her nipples! Pretty risqué for that era. When she became Charles' mistress, she had to give up being the mistress to two other courtiers (but she kept a third, the Royal Chamberlain and fellow advisor to the king, Pierre de Breze).

The king showered her with gifts, such as the Château de Loches, and had her painted as the Virgin Mary, with one breast bared, for a diptych at Melun. She became the first official mistress in a long line of French kings. She helped Charles to conquer his depression and transformed him from a timid, indecisive king into a strong ruler. She met an untimely death by mercury poisoning shortly after giving birth to her fourth illegitimate royal daughter. She was only 28 years old. Charles' estranged son, the future Louis XI, was suspected, but it was never proven. She was only the king's mistress for six years, but those were Charles' most prosperous years.

Besides the Velouté Agnès Sorel, Escoffier also included Suprême de Volaille Agnès Sorel (Breasts of chicken in a Madeira sauce on a bed of rice flavored with truffles, mushrooms and tongue) into his Guide to Modern Cookery. How appropriate for the woman with the most beautiful bosom in 15th century France!

Sources: Wikipedia; http://www.medadvocates.org/celebrati/february/feb_09.htm

Sole Véronique

The opéra comique Véronique was composed by André Messager in Paris in 1898 and was widely performed in London and Paris for fifty years. Eventually, it  was performed in all the major capitals in Europe. Vicomte Florestan is forced by his uncle to either marry or go to debtor's prison for his overspending. He chooses an arranged marriage to Hélène. She has never seen his intended, but goes to a florist to buy her corsage before the ceremony. By coincidence, Florestan goes there too. She overhears Floristan's conversation and discovers that she is his intended. Hélène changes her name to Véronique, and comedy ensues. Escoffier created a new dish at the London Carlton to celebrate the long run of the play: Sole Véronique.

was performed in all the major capitals in Europe. Vicomte Florestan is forced by his uncle to either marry or go to debtor's prison for his overspending. He chooses an arranged marriage to Hélène. She has never seen his intended, but goes to a florist to buy her corsage before the ceremony. By coincidence, Florestan goes there too. She overhears Floristan's conversation and discovers that she is his intended. Hélène changes her name to Véronique, and comedy ensues. Escoffier created a new dish at the London Carlton to celebrate the long run of the play: Sole Véronique.

Source: Wikipedia

Poularde La Tosca

Buried in his work while at the London Savoy, only getting four to five hours a sleep a night, with his wife and family away in France, Escoffier could at times be a lonely man, but always a private man. He did have one great admiration, and that was for Sara Bernhardt. They had been friends for years and he knew all her stage roles by heart. It was well known that she admired him as well and was one of her favorites. She would have Auguste prepare scrambled eggs accompanied by Champagne privately for her birthday dinners. There has been much speculation if they were lovers, but Sarah usually would comment on her leading men. Her powers over men was magical. Her biographer wrote "For Sarah, to admire a man was, as often as not, to sleep with him" and she would usually talk about her conquests. But, showing discretion unusual for her, all she would ever say about Auguste was that he made the best scrambled eggs in the world. So it was never proven that the two were more than just great friends.

|

|

| Bernhardt around 1878 | Sarah Bernhardt in the title role of the play La Tosca |

Sarah would stay at the Savoy for long periods at a time, and Auguste would design recipes for her. Poularde La Tosca was created when she was playing the title role for the play (not the opera) La Tosca by Victorien Sardou in 1887. Puccini's opera was based on this five act play. It is interesting that in Act 2 of the opera, the villain Baron Scarpia, of intemperate appetites, eats from a table which, besides being laden with food, also has cutlery. Tosca later uses a knife from this table to dispatch him.

Poularde La Tosca is a whole chicken stuffed with truffled rice pilaf, roasted and served with braised fennel. But this was not the only Escoffier recipe with a Tosca theme. Consommé Tosca, Tartlettes Tosca, Saddle of Veal à la Tosca, and Bombe Tosca can be found in his books. Other dishes were named for Bernhardt directly, such as Escoffier's Potage Sarah Bernhardt and Fraises à la Sarah Bernhardt.

Sources: Wikipedia; Escoffier: The King of Chefs by Kenneth James; The Boston Globe: A real- life Diva Gave Tosca Some of its Flavor.

-

Articles

- Cuisine of the Sun: Cuban Cuisine and Restaurants in Greater Miami

- The “American Riviera” Santa Barbara – splash, scenery and splendid sipping!

- The beginning of a love affair to remember – Thomas Jefferson ❤ Wine

- John Locke: politician, philosopher... oenophile?!

- The splendid wines of Virginia

- Ten tips for dining out: Refining our favorite pastime

- Lady Swaythling and The IW&FS

- The 1870 cellar of Charles Dickens

- A delicious history - Gelato past to present

- The splendid wines of Portugal

- One Oenophile’s Opinion . . . On Cellar Temperature

- Tasting the grape styles of California

- Building a wine cellar – don’t be afraid!

- Vancouver Dreaming

- Is it coffee–or is it Puerto Rican coffee?!

- Matching Wine with Food

- Malbec, the Summer grilling wine

- Champagne on the Rocks?

- Sauvignon Blanc - Better than Chardonnay in wine-food pairings?

- The Origins Of Our Great Society

- An Evening with Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson - A Summary

- Auguste Escoffier: Founder of Modern Cuisine

- Island Traditionalists and a Mainland Maverick Wines of Dalmatia

- Eastern Europe Wines & Dining

- Wines of Croatia Part II

- Agoston Haraszthy: American Entrepreneur & Founder of California's Oldest Premium Winery

- Rare Discovery of 18th & 19th Century Madeiras at Liberty Hall

- Left Over Wine?

- Dinner in the Diner During the Golden Age of Rail Travel

- Missing The Boat